Progressive Overload—Outdated?

By: Josh Bryant

One day, my first powerlifting mentor, Steve Holl, took a cursory glance around Santa Barbara Gym and Fitness. Then he said, “Look around this gym. The same people lifting the same weights, doing the same exercises, and looking the same for the past 15 years.” After a slight shake of his head, he added, “If you take one thing away from today, remember, you gotta put more weight on the bar. No matter what you do, you have to put more weight on the bar.” Of all my in the trenches and academic learning, that conversation in 1995 has had the biggest influence on me. Steve’s observation was disgust at the total disregard for the overload principle. Milo

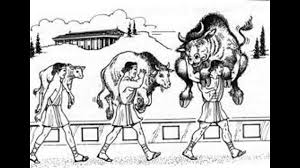

Milo of Croton was a wrestler with several ancient Olympic titles under his belt, considered by most historians as the greatest wrestler of antiquity. Milo’s heyday was 6th BC but to this day his name is associated with strength. Milo built his strength by using progressive overload before it was a categorized as a granddaddy law or principle at all. Milo had a baby bull or a calf; Milo lifted that calf every single day, as the calf grew bigger, Milo became stronger. Milo did this all the way until the calf was a full grown bull and then he was the strongest man in the world. Milo eventually carried the adult bull on his shoulders around the Coliseum. Milo started small, used micro progressions daily and became the strongest man in the world. Progressive overload worked then and it works now. Why Progressive Overload? The law of overload is one of the first principles learned in exercises physiology. It means: Mother Nature overcompensates for training stress by giving you bigger and stronger muscles. Progressive Overload is one of the Seven Grand Daddy laws categorized by Dr. Fred Hatfield. No resistance training program will be successful without progressive overload at its foundation. Overload Misapplied It’s common to hear, “If something is working well don’t change a thing.” If training is going well now, this mindset will halt progress quickly. Changing something means intensifying training and this has been bastardized to the umpteenth degree. Think of all the crazy exercises like doing squats on bosu balls; if you’re an alpine skier I can see rationale. But if the objective is to get stronger or gain size, that’s down right stupid and dangerous, science and common sense concur. Unfortunately, at the expense of results, celebrity trainers perpetuated entertainment over what works to keep clients interested; maybe they are hoping since Coney Island was put on the map by bizarre tricks they can follow suit. They should realize their clients will stay interested if they helped them get great results with what’s proven to work. Think about it. If you constantly change things and total randomize training, how in the hell will you continually overload? It’s as logical as the temperance society inviting Popcorn Sutton to give a

speech. Overloading needs some sort of quantitative assessment. Progressive Overload Misapplied Overloading your training is not my opinion, it’s a granddaddy law. I don’t make the rules. Many times the bizarre “functional training” realm will dismiss progressive overload with randomization. After all, why squat when you can do one-legged occluded goblet squats on a trampoline holding a kettlebell overhead? The bodybuilding crowd will attempt to dismiss progressive overload with constantly changing exercises for “confusion.” Because of the repeated bout effect, this logic is sounder than the functional training crowds, but misapplication was seen recently when a pro bodybuilder was having clients doing leg presses with sliders on the leg press to activate different parts of the quad. For the bodybuilder, more frequent exercise rotation is needed but when cycling exercises, you need to overload them from when you performed them last. Keeping a training journal makes this simple. Strength Coaches Prominent strength coaches have talked about progressive overload being outdated, which is downright silly. If you do not constantly overload your training you will not get stronger. Their idea is if someone bench pressed the bar today and improved five pounds a week for three years they would bench press 825 pounds, 103 pounds over the most weight ever bench pressed. Linear progression without deloads, using the exact same rep scheme and set scheme, will run someone into a wall. Mel Siff offered a solution with what he called periods of increased loading, in essence, cycling training. You do a 12-week linear cycle by gradually decreasing reps; if every time you use 8s, use more weight than you did last time with 8s. Westside barbell uses progressive overload. Think about it. By rotating a ton of specialty exercises, let’s say for a max effort squat/deadlift, one does safety box squats off a 14-inch box for a max double, the objective is to beat the record set last time. If this exercise was last performed six months ago with 405 for a max double, it better be 406 or more now. Any system that is effective at building strength progressively overloads. Training, meaning working toward a long-term goal with purpose and long-term adaptations in mind, requires progressive overload. Remove progressive overload and you are working out. This means exercising for an immediate feeling. Working out is fine to slightly improve health but if you have the slightest desire to take this to the next level, training is required. Since we cannot just continue to pile weight on the bar without stalling out, let’s explore seven alternative options to overload training. 1) Load (resistance) increases—The most obvious way. Don’t think in terms of adding 45s and 25s to the bar, this is what bodybuilders with small IQs and Big Egos do. Adding five pounds a month to a lift will increase the maximum by 60 pounds in a year. Amazon sells one-pound plates. Think micro progression for long-term gains.

2) Increase Volume—simply do more. This could be an increase in the amount sets performed, weight lifted or repetitions performed. Volume is (sets x rep x weight lifted). Do not do this with light weights under 65 percent of a one-rep max. Obviously, bench pressing 100 pounds for 10 sets of 10 provides a different training effect than bench pressing 500 for 10 sets of 2 reps, although both are 10,000 pounds of volume. 3) Increase Range of Motion—Doing a snatch grip deadlift with 75 percent of a one-rep max deadlift is much more difficult than a regular deadlift, try deep Olympic pause squats instead of power squats, use a cambered bar on bent over rows……..examples could go on forever. 4) Alter Repetition Speed—Slow down the eccentric and prolong time under tension, speed up the concentric and take force production to a whole new level. 5) Shorten Rest Intervals- Do the same amount of work in less time or do more work in the same amount of time. Both increase training density, a very legitimate way to overload training. 6) Change Exercises- For strength athletes, the core lift competed has to stay at the nucleus of the program. For most bodybuilders a variation of the core lifts needs to be at the nucleus of the program. More frequent changes in exercises are needed when hypertrophy is the objective, but pure strength accessory exercises can be changed every couple blocks. 7) Increase Frequency-Train more often.

Final Thoughts

One of the best markers of a good coach is how well they can overload an athlete’s training without making the training a side show. These are some of the overload variables I look at with program design, there are many others, but this is a good starting point. The idea is to load linearly as long as possible, then start pulling more tricks out of the hat as one journeys from beginner to intermediate then to advanced training status. In the tradition of Milo, I wish you success with progressive overload. Jailhouse Strong offers an easy to follow, results-producing, progressive overload model.