Build Starting Speed

by: Josh Bryant

Whether you are chasing down some carny-looking meth head, attempting to gank a catalytic converter outside of Waffle House or pursuing Grid Iron Glory, you rarely ever reach top speed!

Therefore, starting speed and acceleration are the most important components of sprinting. Think of “starting speed” as that “first step”.

Intriguingly, to this point, many shot putters are faster than sprinters for the first 30 meters of a sprint. The best way to improve starting speed, besides improving your strength-to-bodyweight ratio, is with short sprints at five to 10 yards. Start in a specific position and simply sprint through that distance.

Improving acceleration goes hand and hand in training for starting speed. Short sprints improve acceleration. However, improvement in acceleration will be gained with slightly longer sprints. Remember, the ability to reach top running speed efficiently is more important than the actual top running speed.

Focusing on acceleration is the key to developing explosive speed. There are two running drills that can immensely help. Start with longer than 10 yards (15 to 25 yards is a good starting point), the focus here is on increasing stride frequency. The second drill is to jog a short distance before exploding into a full sprint, this is sometimes called a flying start.

Ground Contact Forces

The most important factor to work on to increase your start, acceleration and even top end speed is to increase “ground contact forces”. These forces are determined by the speed-strength of muscles pushing action in the start as well as by acceleration, maximum speed, and speed endurance.

Strength-to-bodyweight ratio is crucial here.

Ground contact forces determine the maximum speed an athlete can reach. For each pound of bodyweight, 2.15 pounds of additional ground contact forces are needed to maintain an athlete’s starting speed, acceleration, and top end speed. So, a bulking tactical athlete that gains 10 pounds must be able to produce a minimum of 21.5 pounds of ground contact force to maintain speed (regardless of the composition of added body mass), hence the difference between hypertrophy and “tactical hypertrophy.”

The conventional deadlift and squat are two technically simple ways to test for the ability to produce ground contact forces. Generally, athletes will get faster by default as their strength-to-bodyweight ratio improves in these lifts to 2.5 times their bodyweight; that is why this I have hailed this the gold standard of limit strength for the tactical and traditional athletes in these movements.

Sprinting Loading

The goal of sprint loading is to make sprinting more difficult and for it to transfer to faster sprints.

Sprint speed is improved by sprint loading primarily by the following two means 1) increased physical output i.e. increased production of triple extension force and power and 2) improved physical efficiency output.

Renowned researchers JB Morin and colleagues summarize the determinants of sprint acceleration as “technical ability to apply horizontal force”, sprint loading is a tool that potentially increases the ability of horizontal force production.

By adding resistance when sprinting, an athlete is provided with less braking forces and a longer opportunity for forward trunk lean resulting in a chance for horizontal force application. Athletes do spend a longer time on the ground with resisted sprint training, this provides more time to produce horizontal forces.

A 2016 review published in the Sports Medicine Journal, confirmed that 10 out of 11 peer-reviewed papers on resisted sled sprint training (RSS) showed improvements in either acceleration or maximal velocity sprint performance. Interestingly, some of the sled loads in this review were up to 43 percent of the participant’s bodyweight, discrediting the myth that heavy sleds make you slow!

Another 2013 study compared the effects of compared the effects of combined weighted sled towing and sprint training against traditional sprint training on 10 and 30 m speed in professional rugby players. Each training group completed two training sessions per week for six weeks, with performance reassessed post-training. The combined group that trained with weighted sled towing had greater improvements in sprint speed.

My two favorite sprint-resisted training modalities are:

- Hill Sprints

Hill sprints allow athletes to train at maximal velocities in a much safer manner than sprinting flat surfaces because the slope of a hill shortens the distance the legs have to land, and reduces impact. This makes it safer for aging tactical athletes (a population I frequently use hill sprints with, along with those new to sprinting). Hill sprints improve the drive phase, which, in turn, helps reach maximum speed faster.

Why tactical athletes? Because cops are not immune to foot pursuits up hills and recent military conflicts have taken place in mountainous terrain, making hill sprints even more specific to tactical athletes. Hill sprints are valuable for building acceleration and top end speed. When training hills for maximum speed, keep the distance 40 yards or less and allow for a full recovery between sets.

2. Sleds

Sleds are dragged behind an athlete or pushed with the weight in front of the user, both are very effective modalities for building acceleration. Weighted sled sprints training specifically works the muscles used while sprinting and helps bridge the gap between weight room exercises and running drills. Weighted sleds teach athletes how to produce the type of force that moves them forward. When training sleds for maximum speed, keep the distance 50 yards or less and allow for a full recovery between sets. There are no universal resistance recommendations; as long as biomechanics are not faulty, the weight is not too heavy.

Final Thoughts

Starting speed and acceleration are the name of the game when it comes to sprinting for most sports and real-life situations, build these qualities with sprint loading!

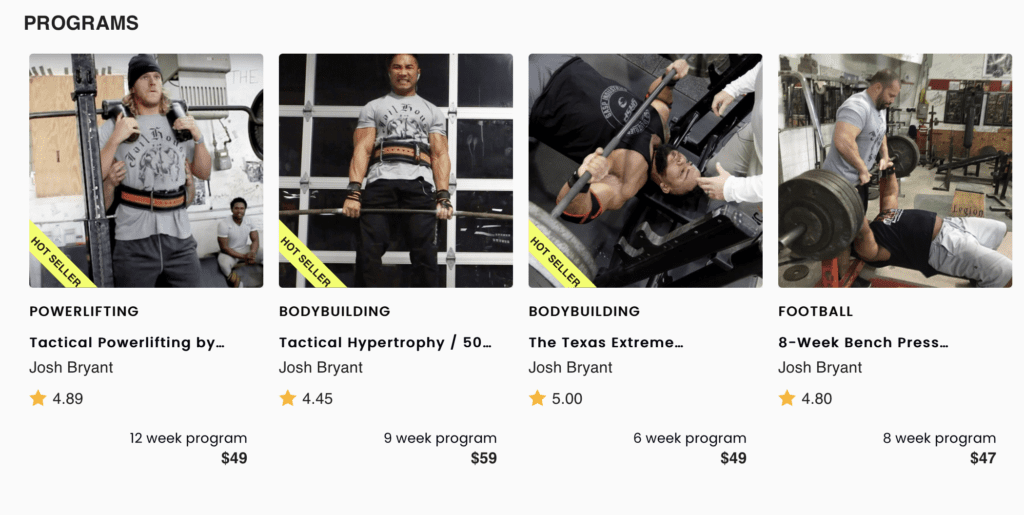

Get faster with one of Josh’s programs HERE!