Harnessing the Power of PAP—Practical Application

By: Josh Bryant and Joe Giandonato

Fred Hatfield utilizing post activation potentiation (PAP) pre-deadlift

If you want to take a good look at a T-bone steak, you can stick your head up a bull’s ass or take the butcher’s word.

If option one is needed, please review last week’s newsletter. Otherwise, T-bones, anyone? Let’s get to the meat of how PAP can be used here and now to become stronger and more explosive.

- “PAP” Your Way Through Plateaus

PAP is not for cats in the dog pound or novice athletes. Novices lack the strength and coordination to benefit from PAP and don’t have the work capacity or technical proficiency in various movements used to induce PAP.

As Dr. Squat always said, “You can’t shoot a cannon out of a canoe.”

In the PAP context, this means athletes should establish a solid foundation of limit strength and expand their work capacity to a level where they can execute high-intensity, repeated-effort movements— which are the meat and potatoes of motor learning and hypertrophy.

Don’t start ordering whiskey on a beer budget.

If you want to include PAP into your programming, you need to meet strength standards outlined in the table below:

| Exercise | Strength Standard |

| Squat | 1.5 X bodyweight and be able to perform 2 sets of 8 repetitions with 70% of 1RM |

| Bench Press | 1.25 x bodyweight and be able to perform 2 sets of 8 repetitions with 70% of 1RM |

| Deadlift | 2.0 x bodyweight and be able to perform 2 sets of 5 repetitions with 70% of 1RM |

| Overhead Press | 0.75 bodyweight and be able to perform 2 sets of 8 repetitions with 70% of 1RM |

| Box Jump | Be able to clear platform and cleanly and softly land atop 24-30” height for 5 repetitions |

The first work set of a given movement is to be performed with or close to 90 percent of a one-repetition max with effort quantified as an RPE of 8.5-9 of 10 — this means one to two reps short of failure. This set referred by “bros” as the “top set” because it is the heaviest and requires the greatest amount of testicular fortitude.

Successive work sets are performed at 55 to 85%, but primarily in the 70-75%, if building a stage-ready physique (Chippendales or bodybuilding), aka hypertrophy and/or strength-endurance is the objective.

This is powerbuilding! This is reverse pyramid training!

Now, if enriching explosive power is desired, use a load of 40–70%. For advanced athletes and lifters, whose limit strength is considerably greater, loads ranging from 35-55% performed as “speed work” or utilizing the dynamic effort method, as advocated by Louie Simmons, via work borrowed from Fred Hatfield.

Here is what to do.

If an athlete performs their top set with 315 pounds for 1-3 repetitions. The athlete will then execute subsequent sets, if prioritizing muscle size and strength-endurance between 70-75% (220-235 lbs), or if performing “speed work” between 40-70% (125-220lbs).

This method confers amazing results for NFL athletes performing a bench press reps-max test at the combine — usually yielding two plus additional reps.

When using this methodology for explosive power, always lift the submaximal weights with the intent to move the weight as fast as possible.

- Wave Loading

Wave Loading in Action, With Josh and Jonathan Irizarry at Destination Dallas

For old heads, or experienced lifters in their primes, wave loading can help make them stronger than the best West “by God” Virginia moonshine!

Wave loading, popularized by the late, legendary strength coach, Charles Poliquin, involves gradually building up to lifting heavier weights, often heavier than what your mind and body believes is your current one-rep max, in “waves” of 3 sets each; ultimately peaking with a final wave that violates your current one-rep max like a parking meter.

Poliquin dumbed down wave loading to the masses as a “ramping system used to progressively excite the nervous system” by way of post-tetanic potentiation, an action characterized by proliferated neurotransmission following a brief volley of action potentials which enable muscle contraction.

For an athlete whose current one-rep maximum is 300 pounds, a wave loading scheme would look like this:

| Wave 1 | |||

| Set | Load (lbs) | Repetitions | Rest Interval |

| 1 | 264 | 3 | 3-5 minutes |

| 2 | 279 | 2 | 3-5 minutes |

| 3 | 294 | 1 | 3-5 minutes |

| Wave 2 | |||

| Set | Load (lbs) | Repetitions | Rest Interval |

| 1 | 270 | 3 | 3-5 minutes |

| 2 | 285 | 2 | 3-5 minutes |

| 3 | 300 | 1 | 3-5 minutes |

| Wave 3 | |||

| Set | Load (lbs) | Repetitions | Rest Interval |

| 1 | 275 | 3 | 3-5 minutes |

| 2 | 290 | 2 | 3-5 minutes |

| 3 | 305 | 1 | 3-5 minutes |

- Contrast Training

Noah Bryant, Showing Jump Training for Strength Athletes

Another way to plow through plateaus that doubles down as a later stage preparation tool for athletes is contrast training.

Contrast training simply means the pairing of a traditional strength exercise with an explosively-performed exercise with a lesser load or even no load. The pairings should be performed in the same plane to be force vector compatible; in layman’s terms, this means the movements should be similar in the summation, magnitude, and direction of force.

The selection of which exercises to pair comes down to movement capacity, specificity of desired task or sport, and logistics (i.e. jumps may not be capable in basements and within rooms with low ceiling clearance) but you could always nut up and bang your head against the floor and get some extra neck work in.

So now, as the rubber hits the road, remember, deadlift variations should be paired with broad jumps, approach jumps, or other jumps for distance.

Squat variations are paired with box jumps and other jumps for height.

Supine medicine ball throws, or plyometric push-ups, are paired with bench presses.

Otherwise, lightly-loaded barbells can be used as can kettlebells and medicine balls within the explosive movements.

A sample contrast training protocol can be found below:

| Exercise | Sets | Repetitions | Load | Rest |

| 1A) Paused Barbell Front Squat | 5 sets | 3 repetitions | Weighted barbell | 0:15 |

| Alternate with | ||||

| 1B) Box Jump | 5 sets | 3 repetitions | 1:00 |

- Lifting Big Before the Big Game

The Legendary, Al Vermeil, Interviewed by Josh

The legendary Al Vermeil, the only strength coach to have world championship rings in both the NBA and NFL (and he also did a stint in the MLB), is a huge advocate of this approach. When Al Vermeil speaks, we listen and so should you.

Having overseen strength and conditioning programs at the high school and collegiate levels, we are painfully aware of time constraints student-athletes face. Lifting in-season is non-negotiable to preventing injury, retaining and even developing strength.

Unfortunately, in-season lifting is often an afterthought, especially within the high school and small college ranks. Sometimes, the only time available are the hours or minutes before competition.

Cunningly, we would get a lift in, sometimes as a team or with a group of driven athletes.

Lo and behold, athletes reported feeling rejuvenated following their brief lifting session and research presented in Part I backs this. Brief bouts of circa maximal exertion evoke a potentiating effect — awakening the nervous system and priming it for high performance.

Pre-game training sessions should not be performed by untrained athletes. Unfamiliar movements, progressions, and alternative lateralizations should not be introduced and eccentric stress should be kept to a minimum. Under no circumstances should an athlete attempt a personal record or train to failure on any given set. Sessions should be capped once a main lift or accessory “activation exercises” are completed.

An actual pre-competition training session for a professional basketball player can be found below:

| Exercise | Sets | Repetitions | Load | Rest |

| Lateral Squat to Medicine Ball Slam onto surface of plyometric box | 2 sets (each side) | 3 repetitions | 15 pound medicine ball | 0:30 |

| Barbell Front Squat | 1 set | 3 repetitions | 275 pounds | 1:00 |

| Barbell Front Squats | 2 sets | 3 repetitions | 195 pounds | 1:00 |

| Alternate | ||||

| 1A) Barbell Glute Bridge | 2 sets | 5 repetitions with 3 second isometric at top | 135 pounds and 185 pounds | 1:00 |

| 1B) Band Stomp with Accentuated Knee Extension | 2 sets (each side) | 10 repetitions | Medium band | 1:00 |

Know thyself! This doesn’t work for everyone, this needs to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

- Isometric Contrast Set

An isometric contraction is defined as a muscular contraction not accompanied by movement of the joint. This can range from bodybuilding posing to pushing or pulling against an immovable object.

An often overlooked benefit of isometric training is it leads to the highest activation level of all exercise modes, concentric or eccentric.

Peter Edgette Demonstrates this Methodology at Metroflex Gym in Arlington, Texas

By pushing as forcefully as possible against an immovable object in a weak region, not only are you overloading this region but you are also programming your central nervous to be aggressive. This is in line with an offensive movement intention. By pushing against an immovable object, you will produce a localized training effect within 15 degrees of the joint angle you are targeting, i.e. a sticking point.

Applied

- Perform an isometric contraction against an immovable, strong, solid structure in a sticking point of a particular lift you are targeting (squat, bench press, deadlift or overhead press) or anywhere throughout the lift for activation.

- Don’t start the isometric contraction at the point the isometric contraction will take place. Some dynamic movement is recommended pre- and post-contraction.

- Do not exceed five to six seconds for maximal isometric contractions.

- Perform a submaximal set of the full range of motion exercise (squat, bench press, deadlift or overhead press) work after isometric contractions for one to three reps with 50-75 % of your max as explosively as possible.

- To maximize benefits, contract isometric as hard as possible.

- Rest two to three minutes after each isometric and two to three minutes after each full range of motion exercise.

- Alternate in a contrast fashion between isometrics and full range of motion lifts.

Do two to six sets.

Your beloved paused deadlifts suck hind tit compared to maximal isometrics against the pins! The reason is simple, this way yields greater motor unit activation and programs your central nervous system to aggressively combat sticking points.

Maximal isometrics potentiate your nervous system to produce more force and at a greater rate.

If this works well for you with submaximal weights, you can try it prior to lifting a new one-rep max, like Jeremy Hoornstra did prior to setting a world record.

Final Thoughts

If you respond well to PAP, give these exercise pairings a shot to experience higher jumps, faster sprints and lift heavier weights that will take your game to the next level and leave your opponents in the dust!

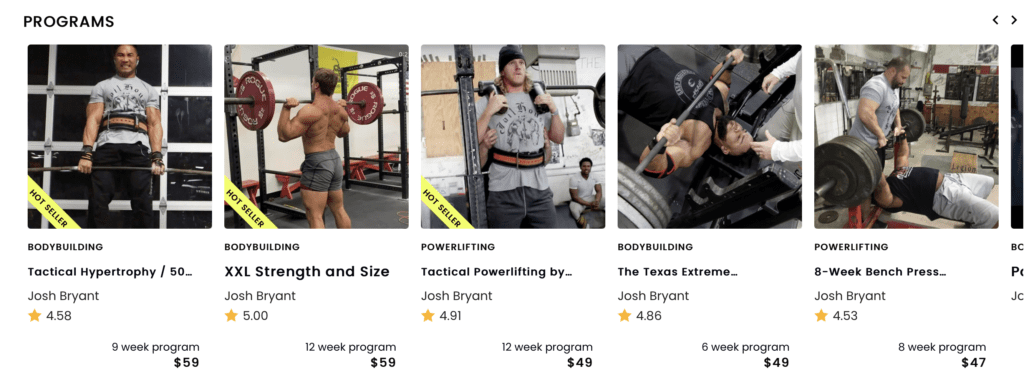

PAP is used throughout Josh’s programs; take advantage by clicking HERE