Mastering Gains: Hardcore Training, Fitness Peaks, and Fatigue Control

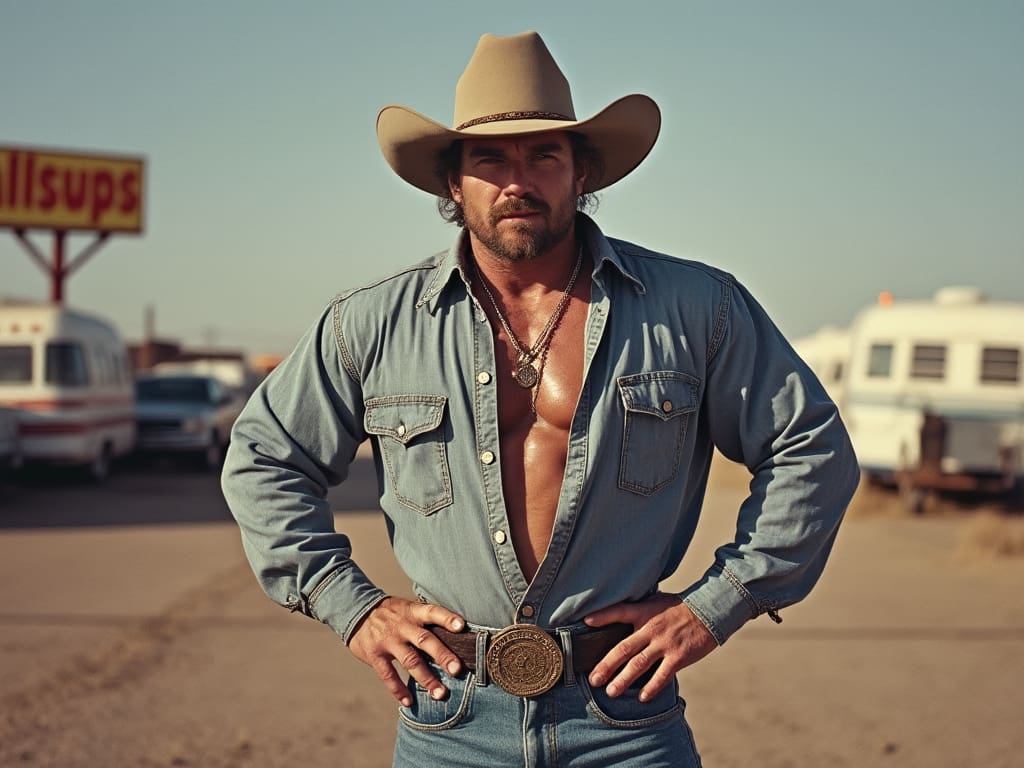

The first time I saw Chuck, he was standing out front of this hardcore gym, set up in an old, abandoned gas station off I-35. He was puffing on a cigarette like it was some kind of performance enhancer, built so chiseled, you could grate cheese on his abs, but he’d probably just use ’em to gut wild hogs, cowboy hat tipped low and a pearl snap shirt half-open. I asked, “Isn’t smoking bad for you?”He smirked and said, “Kid, this ain’t about health. This is about getting strong. Bad is the blonde aerobics instructor leaving without giving me her number. Bad is Waffle House ditching hashbrowns. Bad people are folks who don’t love old dogs, children, or watermelon wine.”

Chuck was a legend, greeting everyone with a gruff “YO,” then heading over to Allsup’s to socialize with the hobos on the train tracks due west after a heavy training session. He lived like some cowboy philosopher, balancing heavy lifting with harder living.When I was a teen, I watched Chuck annihilate set after set in the gym.

One day, a follower of the low-volume, high-intensity Arthur Jones school tried to convert Chuck. For 12 weeks, Chuck swapped out his usual routine for a more “scientific” approach. He packed on muscle, but it was just his body bouncing back from years of overtraining.When the gains dried up, Chuck just shrugged, lit up another cigarette, and went back to his way of doing things. For Chuck, it was always about heavy iron, performance-enhancer cigarettes, and those Allsup’s burritos.

The reality is after this twelve-week period, the gains ceased due to insufficient stimulation and because supercompensation from overtraining was no longer a factor.Poor Chuck, who in this short time became a full-fledged HIT Jedi, flew the HIT coop and like Moses had a glimpse of the promised land but never got to enter.How did this happen?

General Adaptation Syndrome, or GAS, is a single-factor model that describes your body’s short-term and long-term response to stress.

Josh Discusses the Granddaddy Laws:

Put simply, if you hit your body with enough stress (training stimulus), your fitness takes a hit at first, but then it rebounds stronger than ever—welcome to supercompensation. The Fitness-Fatigue Model builds on this, like expanding on Uncle Fester’s moonshine recipe. It’s a two-factor approach to training, dealing with how your body reacts to stress.Let’s say you’re cranking out heavy squats and your thighs start blowing up. That’s the fitness side of the coin. But those heavy sets come with a price—fatigue, like DOMS, creeping up on you after smashing those squats.

The late, great Charlie Francis, sprinting mastermind, used to compare your CNS to a cup of tea. You never want that tea to spill over, or you’re in trouble. Every bit of stress—whether it’s problems at home, lack of sleep, intervals, or even swiping left too much on Tinder—pours more tea (fatigue) into that cup. But if you keep the tea under control, you’ll hit that sweet spot, and boom—supercompensation kicks in, leaving you stronger than before.

Strength Training

When it comes to pounding the iron, volume is a product of poundage lifted multiplied by repetitions multiplied by sets.Percival Ponsonby-Witherspoon, a Waffle House grill master by day and exotic dancer by nightfall, has a 400-pound bench press max.Theoretically, Percival executes three different bench press workouts; session number one is 300 pounds x 3 x 8 sets, resulting in more neural adaptations; session two Percival does 300 pounds x 8 x 3 sets, a more hypertrophic response is induced; and finally, Percival does 100 pounds x 24 reps x 3 sets, this is active recovery.An active recovery/flushing workout can immediately increase fitness, without fatigue. All three of these set-and-rep schemes 7200 pounds of volume, BUT each workout has a totally different training effect.

GAS vs. Fitness-Fatigue

The GAS Principle looks at total volume as the big dog in determining your fitness response. It’s old-school, like thinking benching 225 for 100 reps will make you Hercules. The Fitness-Fatigue model takes it a step further by factoring in both total volume and the intensity of what you’re throwing at your body. Squatting 1,000 pounds for one isn’t the same as squatting 100 pounds for 10, even if the volume’s the same—one makes your body panic, the other is a warm-up.

Overtraining

Every piece of the puzzle—training, sleep, stress, nutrition—works alone, but together they form the perfect storm of fatigue and fitness. Push too much, too often, and you’ve got yourself a snowball rolling downhill. First comes overreaching, which can actually light a fire under your gains (IF properly applied) and followed by a deload. But if you keep hammering, that snowball turns into full-blown overtraining, and good luck recovering from that in just a few weeks.

Final Thoughts

No one’s ever run a four-minute mile and benched 400 pounds in the same week! Training has to be dialed in for specific goals—trying to chase everything at once is like trying to carve spam and prime rib in the same contest. You’re setting yourself up for a mess.Before a big competition, athletes taper off their training to peak at the right moment—this is the delayed training effect, and it’s the backbone of the Fitness-Fatigue model. After brutal training, you need a drop in volume and intensity (a deload/reload) to bring home the bacon, whether you’re a bodybuilder, powerlifter, or tactical athlete.Vladimir Zatsiorsky, back in 1995, broke it down in his book Science and Practice of Strength Training. He said that in an average-intensity workout, fitness gains last about three times longer than fatigue.

So if your body’s fatigue wears off after two days, those gains will stick around for six days. That’s why managing stress and recovery is key—it’s the difference between owning your training and having it own you.Hammer down, train smart, and get those gains.

Train hard, manage fatigue properly, and make gains with one of Josh’s programs HERE.