Explosive Strength—Training Economy

by: Josh Bryant

“Uncle Fester”, as we affectionately named him, wasn’t a good man, but he was good at being a man! Hailing from Western Arkansas, he was a true hillbilly through and through.

Uncle Fester had his “crops” stashed away in the barn, emitting a pungent aroma that could be detected a mile away! Uncle Fester chewed tobacco out of a mail pouch and when it came to his preferred drink, he wouldn’t settle for anything less than the purest moonshine, sipped straight out of the jar.

The rumor has it that he dabbled in chemistry. His neighbors couldn’t help but gossip about the mysterious labs scattered around his property, which tended to go boom every now and then.

Despite his unconventional lifestyle, Uncle Fester was remarkably time-efficient in his moonshine business. He had perfected the art of distillation and could produce top-notch shine in a fraction of the time it took others. His secret was a carefully-crafted process that allowed him to balance quality with speed, making him the go-to moonshine supplier for miles around.

While some might have judged his moonshining as illegal or questionable, one couldn’t deny the efficiency he displayed.

This lesson carried on the weight room.

In strength training, the most bang for your buck is called training economy, and for tactical athletes or traditional athletes, with limited time to train, this is gospel. Building a stronger posterior chain will improve your power clean, but it doesn’t work the other way around. Olympic lifts not only have poor training economy but can also be stressful on the wrists, elbows, and shoulders.

Olympic lift variations are highly beneficial to athletes who perform them pain free with great technique.

If I work with a tactical athlete with great technique in the Olympic lifts and she can perform them pain free, we use the Olympic lifts in her program. The time investment and the risk-to-benefit ratio are not practical for tactical athletes not already proficient in these lifts!

Dr. Bob Gajda, surgeon and 1966 Mr. Olympia winner, had the following observation about power cleans, one of the most basic Olympic lifting variations:

“These coaches hand out these bigger-faster-stronger programs for these kids and tell them to do power cleans. I had seven quarterbacks last year with sprained wrists because they don’t know how to do power cleans. We have all these personal trainers running around America thinking they know how to do it but they don’t. They don’t know the difference between a reverse curl and a clean. And we have to get the old guys back just to teach these kids how to lift weights because they are all hurting themselves.”

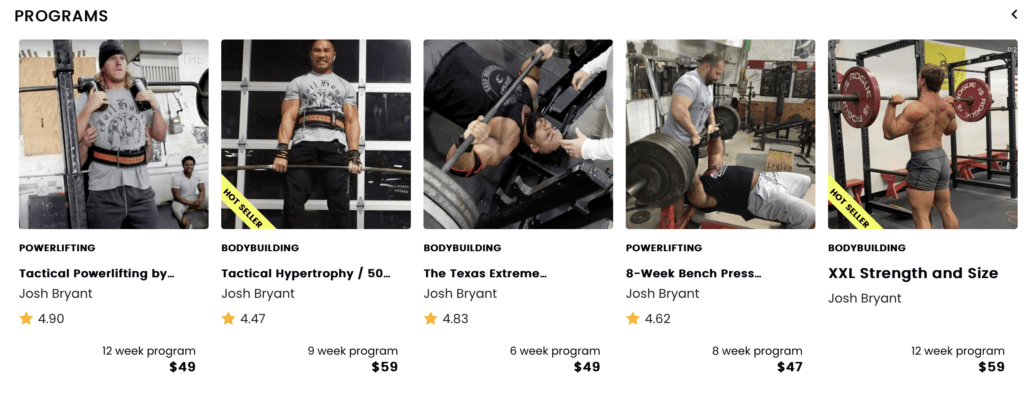

Maximize Efficiency with one of Josh’s training programs HERE.

Triple Extension

The late Dr. Fred Hatfield, my mentor, devised compensatory acceleration training (CAT) i.e. lifting a submaximal weight with maximal force. Louis Simmons popularized Hatfield’s work with his dynamic effort method, the same concept of lifting submaximal weights as fast as possible.

By the late 1990s, a growing but minority of strength and conditioning coaches started using compensatory acceleration training with submaximal weights to build explosive strength as an exodus from the Olympic lifts.

Prior to this, for decades and even today, coaches still argue if the Olympic lifts are a non-negotiable for athletes in pursuit of maximal power production. The reason Olympic variations have such strong advocates is based on the assertion that Olympic lifts produce much higher power outputs compared to powerlifts.

Admittedly, this is true for maximal Olympic lifts compared to maximal powerlifts but the devil is in the details!

Maximal power is obtained with much heavier relative loads with Olympic lifts compared to the relatively lighter loads of one-repetition max in the powerlifts.

Renowned Olympic lifting researcher, advocate and master’s Olympic lifting competitor, Dr. John Garhammer, has demonstrated in research that the highest peak power outputs involved in elite Olympic weightlifters weighing approximately 242 pounds was 4,807 watts of power during certain phases of the Olympic lifts. Another 2005 study that examined the power clean reported maximum power values of 4,230 watts of power, conversed to a 2007 study that showed 4,900 watts of power.

A 2011 study examined 23 rugby players and powerlifters and showed that deadlifts at 30 percent of their one-repetition max produced 4,247 watts of power! This is just behind the values stated by the same researchers in another 2011 study, which showed that peak power in the deadlift was 4,388 watts (at 30 percent of one-rep max) while peak power in the trap bar deadlift was 4,872 watts (at 40 percent of one-rep max). Amazingly, some individuals could reach values over 6,000 watts in submaximal deadlifts!

A landmark 2015 study compared the log clean and press with the clean and jerk and concluded the log lift may be an effective conditioning stimulus to teach rapid triple extension while generating similar vertical and anterior-propulsive forces as the clean and jerk with the same given load.

So yes, properly-executed Olympic lifts catalyze maximal power production but so do submaximal powerlifts. The difference is the learning curve which is much simpler with powerlifts.

Submaximal powerlifts might build power, but what about triple extension strength (extension of the ankles, knees and hips) crucial for running, jumping, throwing and just about any high-speed activity requiring athleticism?

Traditionally, many experts have felt that Olympic lifts were the only strength-training modality that could effectively build triple-extension strength. While triple extension is a key component on the second pull phase of the clean and snatch, watch lifters as they get heavier performing these lifts; they get less and less triple extension because their sole objective is to pull the bar high enough to get under it and catch it, not maximize triple extension. If maximum triple extension is the goal in either of these lifts, the simpler high pull variation that eliminates the catch phase is a better choice.

For a triple extension lifting variant that maximizes power production, I recommend the trap bar jump. In the literature, this movement is correlated with sprinting and jumping ability and better power production than the jump squat. I recommend using approximately 20 percent of an athlete’s one-rep maximum back squat to begin.

Trap Bar Jump Instructions

Watch Josh

Load a trap bar with bumper plates with approximately 20 percent or less of your one-repetition maximum back squat max. Stand in the center of the trap bar with your feet about in your strongest vertical jump stance (usually this is between shoulder and hip width). Bend down and grab the handles, focusing on keeping your hips back, chest lifted and back straight; this is how you start the lift.

- Start the pull by driving your feet into the floor. Extend at the ankles, knees and hips to jump off the ground.

- As you land, keep your knees soft and return the weight to the starting position. Feet should land in the starting position.

- Repeat for the recommended number of repetitions.

Other modalities that can help tactical athletes build explosive power in triple extension movements are jumps, medicine ball throws and strongman events. Which we will take a look at next week.

If Olympic weightlifting made you a better tactical athlete, being a tactical athlete would make you a better Olympic weightlifter!

Get Explosive with Speed Strong HERE!