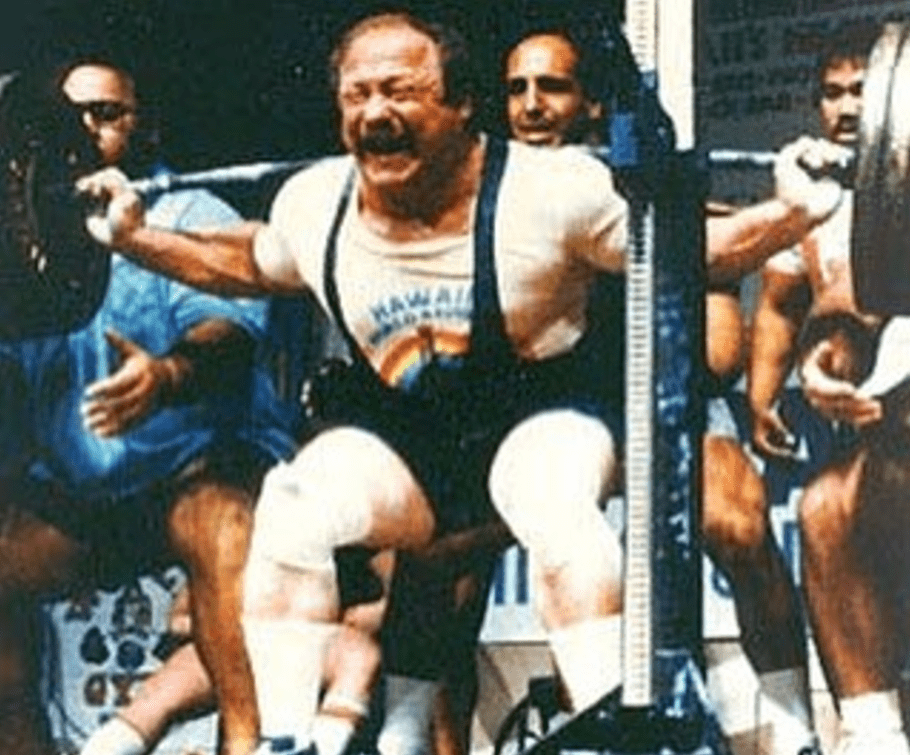

We are honored for the greatest strength training mind of all-time, Fred Hatfield’s contribution

CHEATING MOVEMENTS

Frederick C. Hatfield, Ph.D.

International Sports Sciences Association

The word cheat is used to describe someone who’s trying to get away with something. Someone who’s looking for the easy way, typically at the expense of someone or something else. And the same holds true when the word is applied to training science.

Erstwhile purists of the art and science of bodybuilding state that if you’re cheating, you’re trying to get something for nothing. They say that you’ll end up getting nothing. But they’re wrong.

In reality, the technique can be done the right way or the wrong way, and for the right reasons or the wrong ones.

You can, during training sessions which are designed to emphasize your fast-twitch (white) muscle fibers, swing or heave the weight. That’s one good reason for doing cheating movements. There are two other reasons cited that’re not as good.

Some bodybuilders say that in cheating past a sticking point with a weight that ordinarily couldn’t be lifted using strict form, they’re getting adaptive overload during a portion of the muscle’s range of motion that otherwise may never have received any.

They also point to the fact that, since the weight being used is heavier, the overload is greater.

I reject both points of view as sheer poppycock. If you’re engaged in good, scientific, integrated bodybuilding, the only logical reason for selecting a cheating movement is for better white fiber adaptation.

However, this method of cheating should be done in such a way that the weight is heaved just far enough to get by your sticking point. For example, in doing curls, your sticking point will always be when the elbow is approaching a 90 degree angle.

If you cheat a weight all the way through the exercise movement, you run the risks of 1) muscle, connective tissue or joint microtrauma from ballistic stress, or 2) deriving too little adaptive overload. Swinging the weight all the way through a movement is only productive if you’ve mastered the technique of compensatory acceleration.

Compensating for a joint’s improving leverage as movement continues by accelerating the bar has the net effect of improving the adaptive overload being placed upon the muscle. This is the same rationale used by the manufacturers of both accommodating resistance machines (such as Keiser air machines), and variable resistance machines (such as Nautilus machines).

However, these technologies compensate for improving leverage by controlling movement speed. They’re both excellent. A far more natural way of compensating is to accelerate the bar. In so doing, you’re getting adaptive overload throughout the entire range of motion. And, it’s happening in a way that is not foreign to your body’s motor memory. Mechanically controlled speed is not natural, and therefore foreign to your nervous system.

So, while accommodating and variable resistance technologies are good, compensatory acceleration is better.

Remember, your white muscle fibers can ONLY receive stimulation with explosive movements, so the cheating technique of compensatory acceleration is vital to maximum bodybuilding success.

____________________________

Adapted from Hatfield, F.C. Hardcore Bodybuilding: A Scientific Approach, Contemporary Books, 1993.

AN EXAMPLE OF THE MATHEMATICS BEHIND

COMPENSATORY ACCELERATION

Let’s assume that you’re going to do 5 sets of 5 reps in the squat using the conventional method of moving the weight. That is, push hard out of the hole, and ease up as your leverage improves throughout the upward movement.

First Set I I I I I

Second Set I I I I I

Third Set I I I I I

Fourth Set I I I I I

Fifth Set I I I I I

First Set: The bottom of the last rep in the first set is tough enough to be considered adequate overload to force an adaptive response. The preliminary four squats were not sufficiently intense to force an adaptive response.

Second Set: Ditto the First Set.

Third Set: The bottom half of the last two reps are now tough enough.

Fourth Set: The bottom half of the last three reps are now tough enough to force an adaptive response. You’re getting fatigued.

Fifth Set: Ditto the Fourth Set.

The Mathematics: You’ve achieved overload stress sufficient to force an adaptive response in only ten halves of the 25 squats performed, an efficiency rating of only 20 percent.

Now let’s assume that you’re going to push as hard as you can against the bottom of the bar every inch of the way upwards out of the hole to a nearly erect position (stopping the acceleration sufficiently before lockout so as to avoid ballistically throwing the bar off your shoulders.

First Set I I I I I

Second Set I I I I I

Third Set I I I I I

Fourth Set I I I I I

Fifth Set I I I I I

The Mathematics: You’ve succeeded in achieving overload stress sufficient to force an adaptive response in every single squat yuou performed, every inch of the way. Your efficiency rating is now nearly 100 percent.

You will now accomplish in 1 year what used to take five

years to accomplish.

…in 1 month what used to take five months…

…in 1 workout what used to take five workouts..

…in 1 set what it used to take five sets.

]]>